One of my all-time favorite books is “The Drunkard’s Walk. How Randomness Rules Our Lives.”

I am a big fan of randomness – or more accurately – how we mistake randomness for causation or how we continue to ignore the effects of it in our decision-making process. Seems many of my favorite books are about randomness – The Black Swan, Fooled by Randomness, Sway, Predictably Irrational.

While all those books are fascinating reads (I recommend all managers read them all) “The Drunkard’s Walk” had an anecdote at the beginning that really brings home one of the chief causes of poorly planned incentive and reward programs (and possibly compensation strategies as well.)

Fooled by Proximity

The author, Leonard Mlodinow, recounts a story about flight instructors for the Israeli air force who disagreed unanimously with a speaker who was highlighting the benefits of rewards over punishment for modifying the behavior of the instructors’ students. The instructors said their experience was if they praised a student for well-executed maneuvers, the next time they performed worth. But if they yelled and screamed at them when they did poorly, they almost always did better the next time.

[Sound familiar? Boy – if I had nickel for every time a client told me a similar thing about motivation I’d have a a whole bunch of nickels!]

The instructor, who was using evidence from animal studies, couldn’t understand the disconnect. Why would the studies he’s seen say rewards work better but the experience from the instructors indicate the opposite?

The thing the instructors didn’t realize was that while the yelling preceded the performance improvement it did not cause it.

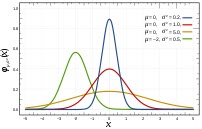

Warning – Statistics Talk Ahead

We like to think that because two things are closely related they are causal. When you get up in the morning the sun comes up. Did our rising cause the sun to come up? Not likely. The answer to the disconnect was found in something called “regression toward the mean.”

Normal Punctuated by the Abnormal

Regression toward the mean simply means that in any series of random events an extraordinary event is most likely going to be followed by an event closer to the normal or ordinary type of event. In this example, when a pilot had an extraordinarily good landing, it would most likely be followed by a landing closer to their normal performance level which would be a worse landing than the previously extraordinarily good one.

Regression toward the mean simply means that in any series of random events an extraordinary event is most likely going to be followed by an event closer to the normal or ordinary type of event. In this example, when a pilot had an extraordinarily good landing, it would most likely be followed by a landing closer to their normal performance level which would be a worse landing than the previously extraordinarily good one.

Same with an extraordinarily bad landing – it would be followed by one closer to their normal level – in this case – a better landing.

So, the instructors, looking back on their experience concluded that when someone had a great landing and they praised them – their next landing was worse.

Yet when someone had a bad landing and they yelled – their next landing was better. What else would they to conclude?

Praise doesn’t work, yelling does. (Now do you see why this stuff is so fascinating!)

Application Time!

We’ve all heard about “management by exception” – the process by which you concentrate on the things that fall outside expected ranges. A very smart way to manage a machine when we want to produce specific parts within specific tolerances (can anyone say Six Sigma?) Not a smart way to manage people. But Six Sigma doesn’t translate well to people – yet managers try to do this all the time.

Think about it. Many managers will believe their own experience mirrors that of the flight instructors. Their own employees react to threats and screaming with improved performance and rewards don’t seem to hold performance at a high level for very long.

Good managers know that performance varies. There will be days of good landings and bad. But the key is to look at performance as a series of events – trend lines – not individual data points. Recognize good behaviors to continue to reinforce what you WANT to continue to happen. And hold “punishment” until you see a trend that indicates “average” performance is suffering.

Don’t overact to a single performance failure.

[Initially written in 2008 and updated a bit for today. Some stuff is just evergreen.]

Recent Comments